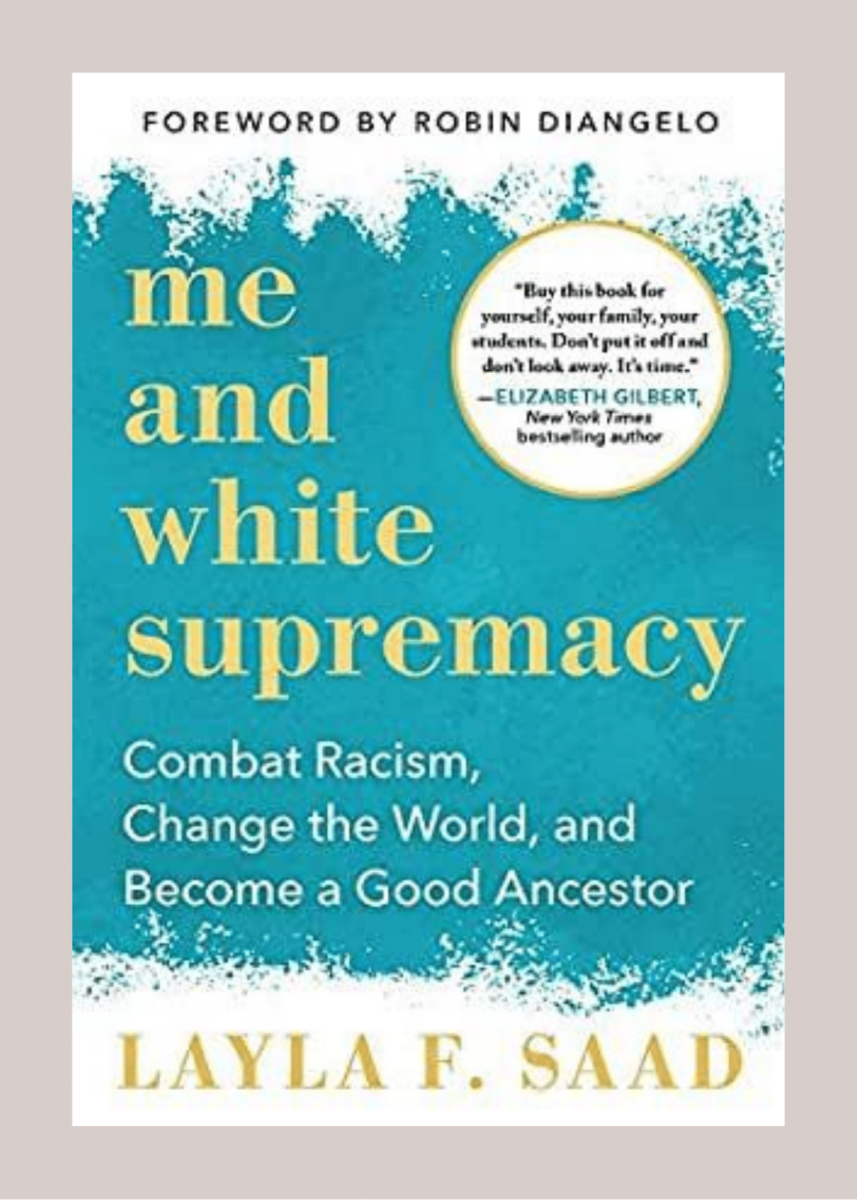

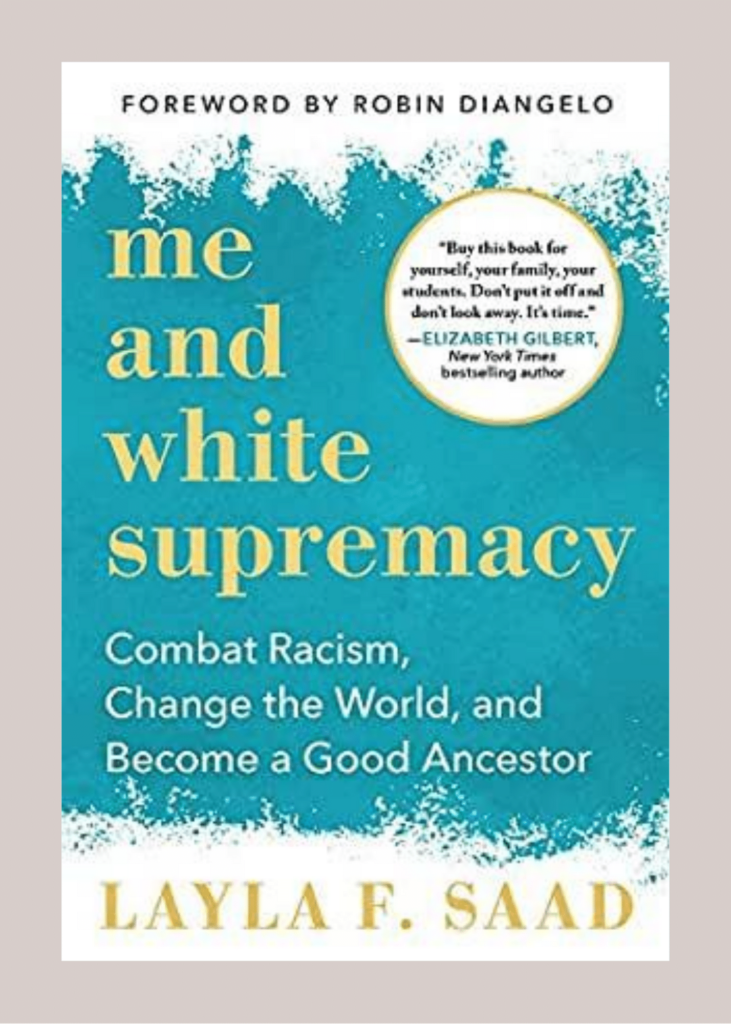

Me and White Supremacy

This was not an easy post to write. This book was not easy to read. The prompts at the end of each chapter were not easy to answer. That’s exactly why I’m recommending Me and White Supremacy by Layla F. Saad.

When George Floyd was murdered and a wave of activism spread across our country and the world in late May/early June, I was outraged. I did what I could to financially back GoFundMes for protestors’ bail funds, Minneapolis Black-owned businesses and George Floyd’s memorial fund. I wrote emails to my elected officials. I signed petitions. I took a week off of posting and instead shared Black creators and Black-owned businesses. I had conversations with family and friends about BLM, what defunding the police would mean, and other topics I hadn’t really broached before, especially with older and conservative members of my family.

A phrase I’ve seen on social media graphics this summer is that white people need to “do the work.” I thought all of that ^ was the work. Boy, was I wrong.

I realize now, after reading this book and going through every chapter’s journal exercises, that what I viewed just months ago as a good response for me as a white ally is now exposed as partial optical allyship.

The work is examining your role in upholding white supremacy, from the macro level to the micro level. I’m not going to lie to you. Sometimes, this book made me angry. It made me want to throw it across the room to stop the feeling of guilt. It made me incredibly upset with myself to the point of tears. But this book, my friends, helped me do the work.

Part of the continued work I will do every day going forward to be a white ally is by encouraging you to pick up a copy of this book and also do the work.

Just by reading this book and writing this post, I am not magically 100% anti-racist – but I am able to have better understandings of the history of white supremacy, see it in action in ways I hadn’t before, and have actionable steps for myself in improving as an ally. The book opens your eyes, and it’s what I do now that I have seen things I can’t unsee that is important.

I normally go over Roses and Thorns of our book club reads. With this book, I’d instead like to share some passages from Me and White Supremacy that really struck a chord.

“‘They can’t mean me. I voted for Obama. I have Black friends. I’ve had partners who are BIPOC. My kids play with nonwhite kids. I don’t even see color! When they talk about racism and white supremacy, they must be talking about those other kinds of white people. Not me. I’m one of the good ones.'”

“When you say ‘I don’t see color’ to a BIPOC, you are saying ‘Who you are does not matter, and I do not see you for who you are. I am choosing to minimize and erase the impact of your skin color, your hair pattern, your accent or other languages, your cultural practices, and your spiritual traditions as a BIPOC existing within white supremacy.'”

“All people, regardless of race, can hold some level of prejudice toward people who are not the same race as them. A person of any race can prejudge a person of any race based on negative racial stereotypes and other factors. Prejudice is wrong, but it is not the same as racism. Racism is the coupling of prejudice with power, where the dominant racial group (which in a white supremacist society is people with white privilege) is able to dominate over all other racial groups and negatively affect those racial groups at all levels–personally, systemically, and institutionally.”

“Do you give more credence, respect, worth, and energy to people with white privilege and white-centered narratives over BIPOC and BIPOC-centered narratives? Do you question, dismiss, or feel ambivalence toward BIPOC when they interrupt your white-centered world view? Do you make an intentional effort to interrupt white centering when you see it, such as by demanding more representation of BIPOC? During your antiracism work, do you focus more on how you feel over what racism feels like for BIPOC?”

“It is normal for any person who has been informed (whether through being called out or called in) that they have caused harm to become defensive, especially when causing harm was not intended. We all react the same way: sweaty palms, accelerated heart rate, the “warm wash of shame” coming over us (as research professor and author Brene Brown calls it), feeling nauseous, and an immediate reaction to want to stand up and defend ourselves by explaining our intentions. Believing we are under attack, our brains react quickly with a fight-or-flight response, causing a cascade of stress hormones to be released into our bodies. However, these feelings are more exacerbated during racial conversations because of the existence of white fragility, white superiority, white exceptionalism, and so on. While call outs and call ins never feel good, they are an invitation to become aware of behaviors and beliefs that are hidden to you, and they are an opportunity to do better so that you can stop doing harm and make amends for the pain caused.

We have all had the experience of stepping on someone’s foot or bumping into someone and immediately apologizing. It was not our intention to hurt them, but it is understood that the impact is still that harm was caused. Instead of refusing to apologize because we did not mean it, we rush to apologize because we understand that we have caused pain. This is a very oversimplified explanation of what happens when we cause people harm. However, I find it useful as an easy way of understanding how, when we have caused harm, our impact matters more than our intention. So, when we talk about being called out or called in, a common reaction by people with white privilege is to focus on their intention rather than their impact on BIPOC. This is a form of white centering, which prioritizes how a person of privilege feels about being called out/in versus the actual pain that BIPOC experience as a result of that person’s actions, whether intentional or unintentional.”

I do not want to center this post and conversation on myself and my feelings, but I do want to share that reading Me and White Supremacy will evoke an emotional response. Some days, I was angry, mad at myself for not knowing better, not being able to connect the dots that the book connected for me. Some days, I was sad that I learned more in a day’s reading than years in school and felt like I had been naively walking around the world. Honor your emotions and work through them. Saad’s journal prompts are great at helping you do this. When you dive headfirst into the roots of the emotion, that’s where things “click.”

Our discussions normally focus on plot points, character development and if we approved of the book’s ending. I have had on average 18 women in the previous discussion groups on Instagram. Guess how many reached out to me to participate in this book’s discussion?

One.

I accept the responsibility for this low number.

I know talking about race as a white person can be scary. That’s exactly why before this summer, there were only a handful of posts about race on my blog and socials. I realize (with the help of this book, actually) that this white silence of mine is what led to the low “turn out” for the discussion group.

Yes, race is a heavy topic. No, I won’t always get it right. But it’s imperative that I try. However uncomfortable white people like me may feel in a conversation surrounding race is a drop in the ocean compared to how BIPOC feel on a day to day basis.

I want to share one of my journal entries in this blog post.

If you came to this book thinking you were “one of the good white people” or an ally to BIPOC, how do you feel about that now?

I definitely thought that I was a good ally. I have an adopted Latina sister, and I have seen her experience microaggressions and overt racism. I have always tried to call out these actions. I guess I thought that by being exposed to more racism in our family through Melissa, as opposed to lots of my white friends and family who barely see racism in action, that I was somehow more equipped to be an ally. After finishing this book, I feel horrible for having once believed that. I see now that I was minimizing the experiences of all BIPOC into what I have seen Melissa go through. I also look back at some of my actions, even in recent months, and view them as optical allyship. Finally, this book has shown me that I have let too many comments and situations “slide” with friends and family. I have made too many excuses. I need to call people out, no matter if it rocks the boat, no matter where my family member is from or how old they are. As a white person, it’s my job to help other white people see their privilege – the burden should not be placed on BIPOC after they have been hurt by it.

Me and White Supremacy called me in. It is my hope to use this platform to encourage you to pick up this book, do the work, and implement it into your life.

After working through the 28 days of journaling, I feel like my eyes have been opened, and as Saad wrote, I cannot unsee the things I now see: the ways in which white supremacy is upheld, and how every day for the duration of my life, I am called to help dismantle it in my own head, in the conversations I have, in the interactions I see, in the economy, and in our local and federal government.

I’d encourage you to purchase Me and White Supremacy through a Black-owned bookshop. I have linked to some located in my biggest audience cities below so you can also shop local.

44th & 3rd Bookseller – Atlanta, GA

Black Pearl Books – Austin, TX

Bliss Books & Wine – Kansas City, MO

Brain Lair Books – South Bend, IN

EyeSeeMe – University City, MO

The Lit. Bar – New York, NY

Semicolon Bookstore & Gallery – Chicago, IL

Solid State Books – Washington, D.C.